An old sailing proverb says: “Below 40 degrees south there is no law, below 50 there is no God”

CAPE HORN THE TERRIBLE

There are four or five places all over the world in the presence of which man feels perturbed, surrounded as they are by a perennial mystical aura of spirituality. If, as it is the case of Cape Horn, they are the craved destination, the obliged passage, the insuperable difficulty, everything takes the aspect and the importance of the sanctuary and of the unconsciously supernatural place. After all, its positioning of 55°56′ south and 67°19′ west, the particular orographic formation and the intensity of atmospheric phenomena which surround it, turn Cape Horn unique and matchless. Cape Horn, loved and hated by seamen over the last four hundred years, was named after Hoorn, a small calm town of the Netherlands, not far from Amsterdam, where Willem Corneliszoon Schouten was born. He was the captain of the ship “Unitie” on which he sailed in search of an alternative passage to the Magellan’s Strait and to the Cape of Good Hope, to reach the Far East. Passage was allowed through these two areas only to members of the Company of the Indies as established by the Company itself. Thus, with the sailing vessel that could carry up to a 360-ton cargo and was defended by 19 cannons, he looked for a canal south of Magellan’s Strait to reach the Pacific Ocean.

On January 29th of the year 1616, after a long crossing together with a school of whales and many albatrosses, he discovered a high pointed promontory that he called Hoorn, later called Horn by the English. The fog that surrounded the ship deceived the whole crew: everyone thought it was the extreme southern tip of the continent and not an island as it really is. Its 1,400 feet of harsh rock were admired for the first time by its discoverers. Unfortunately, after landing in Java, nobody believed in them and they were imprisoned for having infringed the Company’s orders. Only after being taken as prisoners back to their mother country, could they assert their rights and spread the news of their geographical discovery. Nevertheless, the route round the extreme tip of the southern American continent was not widely accepted. Even though the stretch of water between Cape Horn and the Diego Ramirez Islands was more than sixty miles wide compared with the few miles of the Strait of Magellan where maneuverability was often difficult, this did not compensate for the violent weather conditions found in the area. Conditions that were unpredictably violent: the first Dutch discoverers rounded the Cape on a calm day as well as the Spanish Garcia and Gonzalo de Nodal who renamed it Cabo San Ildefonso, thinking to be the first ones to see it.

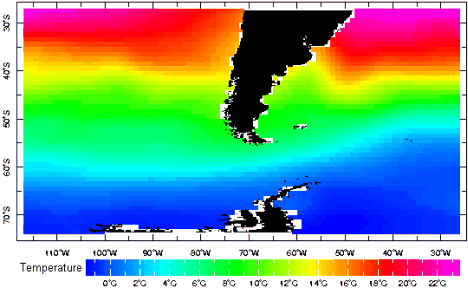

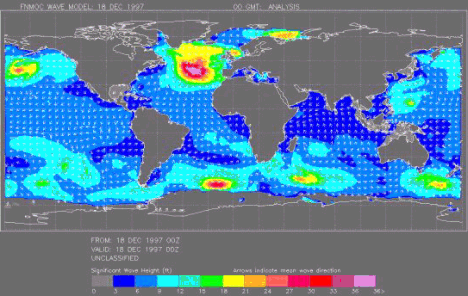

Anyway, only in 1624 it turned out to be an island because of the very few vessels that rounded the cape in the 1600’s. Passages round the cape were more frequent during the following century when the real nature of Cape Horn revealed itself. In 1741, the crew of the English Admiral Anson, in order to take by surprise the Spanish colonies on the Pacific coast, rounded the Cape and lost five of the eight vessels under his command. While Francis Drake circumnavigated the globe, sailing along a more southern course, James Cook and his “Resolution” safely rounded the cape and continued its journey to explore Oceania. The stretch of water around Cape Horn became really crowded from the start of the Gold Rush in California until the completion of the railway lines. The clippers sailed one after the other along the New York-San Francisco route, the same route followed by the best sailors today – including the Italian Giovanni Soldini, onboard his new 60 footer “Fila” – with departure on January 17 from the Big Apple. That was the era of the “cap horniers”, of those who had rounded the terrible Cape Horn. Whoever had rounded the cape bound westward was part of a superior class of men: they were authorized to carry an earring on their left ear or on their chest, and they could urinate to windward. Actually, having sailed through a hostile environment gave them much authority in their field. As a matter of fact, Cape Horn lies where the continental shelf rises from the 13,120-foot deep Pacific bed and where the strong force of the winds that blow around Antarctica often create gales with waves that are frequently more than 65 feet high. The weather forecast of the area announces an average of 200 days of gale and 130 days of cloudy sky and for the rest of the year the wind is strong and the sea is rough.

Many vessels have rounded the cape, but many others have failed. William Bligh, who later demonstrated to be an able seaman when captain of the Bounty, failed to round the cape in 1788. He reached Polynesia by rounding the Cape of Good Hope. The four-mast vessel “Edward Sewall” rounding of the cape lasted from March 10th to May 8th in 1904; “Cambronne” took 92 days to go from one to the other ocean. The rounding of this Cape has not been more perilous than other well-known capes around the world, yet the passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean is complete only after having sailed the 1,000 miles or so that separate the Falkland Islands from Wellington, along the Chilean coast. Whoever arrives from the Pacific Ocean also has to overcome the danger represented by the false Cabo de Hornos, as the Chilean, who politically own the area, call it. This cape is sighted twenty miles ahead and, when surrounded by big breakers and foamy waves that carry powered snow along their crests, may confuse the helmsman who may chose the tragically wrong route. The “funnel”, as Italians call it, attracted and is still attracting modern sailing boats. As opposed to common belief, Joshua Slocum onboard “Spray” was not the first sailor to round the cape, he preferred to go through the Magellan’s Strait despite the difficulties and the hostile natives. The first sailor who really tried circumnavigation was the Australian Clio Smenton who, as a prize after the wreckage of his “Pandora”, received a copy of Slocum’s boat.

The first sailor who really conquered the great Cape Horn was Connor O’Brien, who rounded it with three friends on board the 42 footer “Saoirse”, during the circumnavigation between 1923 and 1925 becoming the first cap hornier in the history of sailing. In 1943, Vito Dumas rounded the cape on board his 31′-long “Legh 2”, but the contemporary attempt of Hal Hansen was not equally successful and the hull of his boat was later found along the coast of Patagonia. More recently, the rounding of Sir Francis Chichester onboard “Gipsy Moth IV” remains unforgettable. He was the first man to sail single-handed around the world with only one stop. His feat inspired the first Whitbread Round the World race, which is today at its seventh edition. At the moment several vessels are participating in the fifth leg of the race which rounds Cape Horn. In the first edition, Bernard Moitessier, after rounding the “Cape” with a good advantage over the second participant, decided to turn back. He returned to the islands of the Pacific Ocean, renouncing the prize of the Golden Globe and £ 5,000 that were waiting for him at the arrival of the race in England. Nowadays, only single-handed sailors and seamen round the Cape which, sometimes, still claims its victims, as was the case of Gerry Roufs in the last edition of the Boc Challenge – his boat was found offshore the Falkland Islands.

Yet, Cape Horn is the most noble symbol of navigation and rounding it approximately twenty times on board the ocean tugboat of the Chilean Army, the ATF Galvarino, has been one of the most exciting experiences that a sailor and lover of the sea as I am might wish. We sailed from Puerto Williams, the southernmost town of the world that lies on the island of Navarino, the last big emerged land, under the command of Captain Fernando Perez Quintas to wait for the boats of the Round the World Race. Cape Horn was calm, sly and well disposed, maybe because of the tribute of the seamen who threw their underwears in the sea, in a sort of counter-spelling habit that this time seems to have worked. The Cape reserved us a thirty-knot wind that lulled in their laziness the surrounding albatrosses with motionless wings around the Cape. Whales, Magellan’s penguins and the “carancho negro” birds of prey completed the faunal picture of the area, which is extremely rich thanks to the cold currents of Antarctica. Even Charles Darwin tried to round the cape, with many risks, on board the “Beagle”, but then he passed behind the islands through the channel, which was named after him, while continuing his studies. Notwithstanding the calm conditions, the captain of “Galvarino” preferred to shelter behind the nearby islands of Hermite and Wollaston, as the Horn archipelago is called, when we had to wait for more than a couple of hours. “The sea conditions here worsen in very short time” he said, based on his experience of months spent sailing in this area and near the Diego Ramirez islands where he later took us to collect the men of the meteorological observation station. These islands, which are seventy miles south of Cape Horn, have always been a point of reference for seamen who had to leave them some hundreds miles back before heading north without running the risk of being pushed by the current toward the dangerous coast of the Land of Fire. It is a sort of highway, bounded by the two lands, that sailing and motorboats have to sail at its center in order to avoid the winding course of the emergency lanes. After the opening of the Panama Canal, this highway is not much used and Cape Horn again dedicates itself to the adventuresome sailors in the races around the world and to its preferred subjects, the lazy albatrosses with their swift enormous wings.